The terms "Harakiri" and "Seppuku" have long captivated the Western imagination, representing an enigmatic, often misunderstood aspect of samurai culture and Japanese history. In this comprehensive guide, we will delve into the nuanced differences, historical accounts, and cultural significance of these ritual suicides.

What is Seppuku?

Seppuku (切腹), also called Harakiri (腹切り), refer to "ritual suicide" and literraly mean "stomach-cutting." This practice of ritual suicide by abdominal cutting has its roots in Feudal Japan. In the Japanese language, both terms essentially convey the same meaning.

Predominantly associated with the samurai class, Harakiri was traditionally executed using a "wakizashi," a type of short sword, or sometimes even a "katana," the iconic longer sword of the samurai. Rooted deeply in Japanese history and culture, Harakiri was considered an act of reclaiming one's honor and was usually committed under circumstances of dishonor or shame.

Unlike Seppuku, another form of ritual suicide, Harakiri tends to be less formal and more spontaneous, often lacking the elaborate ceremonial aspects that define Seppuku. Seppuku is a complex ceremony involving a set of precise formalities and often the presence of spectators and a witness, known as "Kaishakunin."

The concept and practice of Seppuku have both fascinated and perplexed those outside of Japan, giving rise to various myths and misinterpretations. While the act itself is grim, the philosophy and historical accounts surrounding Seppuku reveal a complex social context and a nuanced understanding of honor and shame in Feudal Japan.

What is the Difference Between Harakiri and Seppuku

The terms "Harakiri" and "Seppuku" both etymology mean "Self-execution". Both are forms of ritual suicide originating from Japanese history, particularly associated with the samurai class, but there are subtle differences between the two. The differences begin with the formality of the act, the ceremony involved, and the underlying ethos that drives them.

Seppuku is a highly formal practice often conducted in front of witnesses and involves intricate ceremonial rituals. It is often linked closely with the samurai code of conduct, known as "Bushido," emphasizing honor, integrity, and courage. Harakiri, on the other hand, is generally considered to be a less formal version of the ritual, sometimes performed in more urgent or impromptu circumstances.

While Seppuku requires a witness, known as "Kaishakunin," to perform the decapitating strike, Harakiri may not involve such formalities. Harakiri is also a term widely used by foreigners, but very rarely in Japan, where the term Seppuku is preferred.

The very etymology of the terms also indicates differences: "Seppuku" means "stomach-cutting" in a respectful and formal tone, whereas "Harakiri" uses colloquial language for the same act. Despite these differences, the core act—ritual disembowelment—is the same in both. Both are performed using a short sword like the "wakizashi" or occasionally the longer "katana."

In popular culture and spectacle, Seppuku is often romanticized and portrayed in a way that focuses on the samurai's commitment to honor even in death. Harakiri, due to its informal nature, lacks the ceremonial gravitas but is no less a commitment to the samurai's code.

The key difference ultimately lies in the level of formality and ceremony involved. Seppuku aligns more closely with the formal, social context of feudal Japan, often carried out as a public spectacle. Harakiri is a more direct and expedient means to the same end but lacks the formal ceremonial aspects that make Seppuku a cultural phenomenon.

Is Harakiri a Disrespectful Term?

The term "Harakiri" is often questioned for its level of respectfulness, particularly when contrasted with the more formal term "Seppuku." While both terms describe the act of ritual suicide by disembowelment, associated predominantly with the samurai class, their connotations differ. The term "Seppuku" is more formal and is often used in legal or official texts. On the other hand, "Harakiri" is considered colloquial and more casual.

However, it would be inaccurate to label "Harakiri" as outright disrespectful. The term itself is not inherently pejorative but is rather a less formal way of describing the act. Context matters immensely here. If one were speaking in an academic or ceremonial setting about this ritualistic aspect of samurai culture, the term "Seppuku" would be more appropriate to use. If the context is less formal, then "Harakiri" might be acceptable.

In Japanese culture, where attention to formality and respect is crucial, the use of "Seppuku" over "Harakiri" is often preferred to show reverence for the historical and cultural gravity of the act. Still, the term "Harakiri" is widely understood and is not viewed as disrespectful in most modern contexts, especially outside of Japan.

When was the first Harakiri

The origins of the first recorded instance of Harakiri, also spelled as Hara-kiri, are a subject of historical discussion. However, it is commonly understood to have emerged in feudal Japan, closely tied to the Bushido code that guided samurai warriors. The practice can be dated back to the 12th century, a period when the samurai class was becoming increasingly prominent.

Two of the earliest well-documented occurrences of Harakiri involve Minamoto no Tametomo and Minamoto no Yorimasa, both belonging to the prestigious Minamoto clan. Their acts are also dated to the 12th century, underlining the ancient roots of this ritualistic practice.

These instances were notably recorded during times of war, defeat, or dishonor. The act quickly became not just a method of taking one’s life but a significant cultural practice that spoke to the values of honor, courage, and loyalty to one's master.

However, it's worth mentioning that the historical archive is far from exhaustive. There may well be earlier occurrences that either went undocumented or have been obscured by the passage of time.

What are the Rituals Involved in Harakiri and Seppuku?

The rituals and ceremonies that surround Harakiri and Seppuku are complex and steeped in tradition, each designed to emphasize the act as one of honor rather than mere suicide. Although the terms are often used interchangeably, the ceremonies can differ in formality and complexity.

Seppuku Rituals

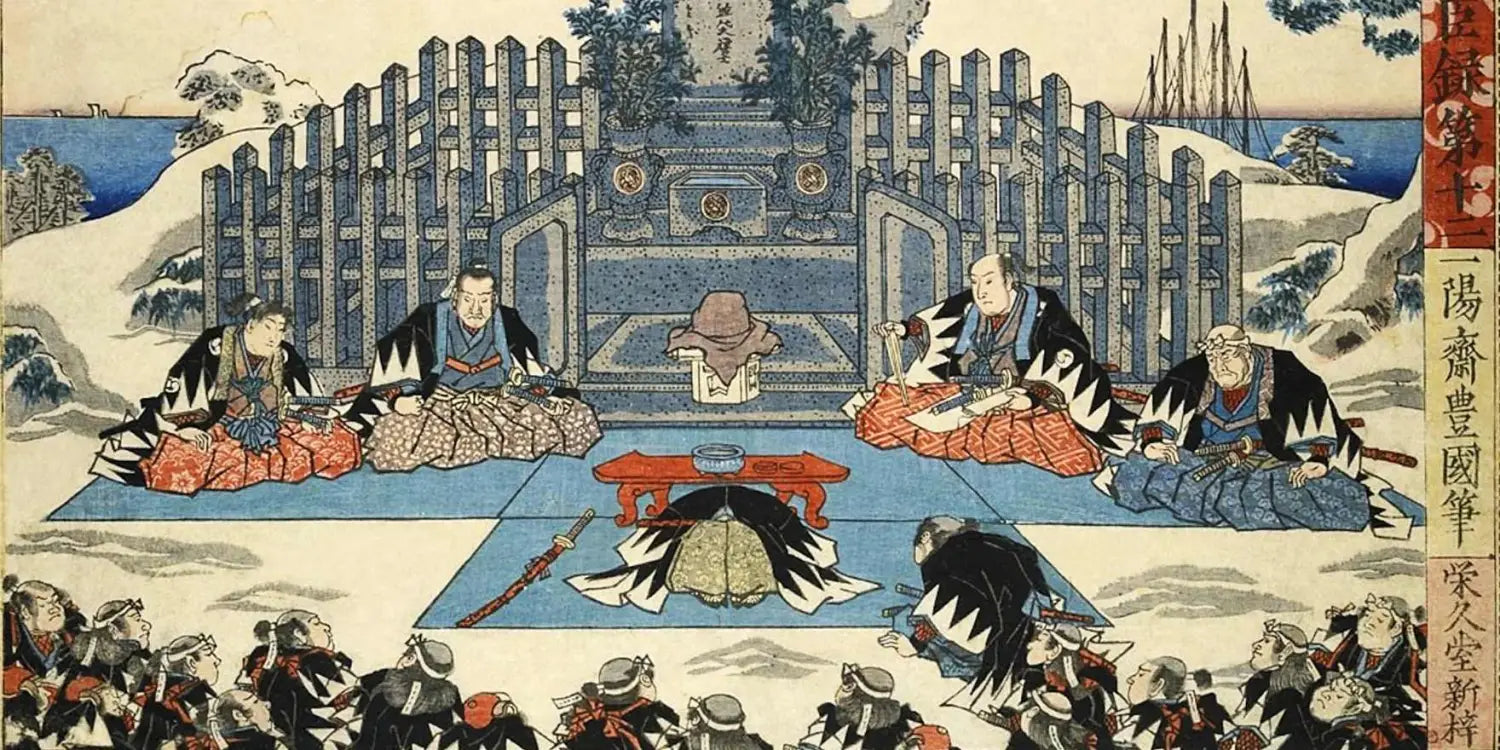

Seppuku is the more formal of the two and is often a highly ritualized ceremony. A typical Seppuku ceremony involves a sequence of very specific actions:

Preparation: The person committing Seppuku would dress in a white kimono symbolizing purity and would be seated on tatami mats. A sake dish would be set before them, and they would write a "death poem" expressing their final thoughts.

Witnesses: Usually, a high-ranking individual would act as a witness, called a "kanshi," and a second, known as "kaishakunin," would be present to perform the mercy strike to quickly end the individual's life.

The Cut: With a tanto or a wakizashi (short swords), the individual would make a left-to-right cut across the belly, sometimes followed by a second cut upward. The kaishakunin would then decapitate them to minimize suffering.

Final Rites: The head and the death poem would then be presented to the witness, and the ceremony would conclude with appropriate rites.

Types of Seppuku Cuts

Jumonji-giri: In this variant, the person would make two cuts to form a cross, and the kaishakunin would not step in. This was considered more painful and was usually reserved for higher-ranking individuals.

Kanshi: In this version, the act would be done in the presence of a superior as a direct protest against the superior's decision. The superior would be expected to take responsibility for the act by committing seppuku themselves.

Harakiri Rituals

Harakiri, being generally less formal, didn't always follow the strict ceremonial traditions that Seppuku demanded. However, it did share many similarities:

Setting: Like in Seppuku, Harakiri would often take place on tatami mats, though it was more likely to occur without witnesses or a ceremonial setup.

Weapons: A tanto or wakizashi was generally used, though some instances involved using a katana.

The Cut: The incision was usually similar to that in Seppuku, though it might be performed with less ceremonial care.

Immediate Circumstances: Harakiri was more often an immediate response to a situation of dishonor or capture and was done quickly.

While both practices have the same tragic end, the ritual and ceremonial aspects of Seppuku are more comprehensive and formal, whereas Harakiri is less so. It should be noted that these practices have long been outlawed and are not condoned by modern Japanese culture.

Are all seppuku the same?

While the central act of belly-cutting remains consistent, there are various forms of Seppuku, distinguished by the specific rituals involved or the circumstances under which the act takes place. Oibara, Tsumebara, Tachibara, Kanshibara, Kamabara, and Kagebara are specific variants that showcase the complexity and nuance embedded in this ancient practice.

Oibara: This form usually involves an elaborate ceremony and is the most formal type. It's often executed in the presence of a high-ranking official or dignitary. A "Kaishakunin" (a second) would be present to perform "Kaishaku," or beheading, to end the samurai's suffering swiftly.

Tsumebara: This is less formal and may be carried out in private or among a smaller group of witnesses. The second may or may not be present.

Tachibara: In this variant, the samurai uses a Tachi, an older style of Japanese sword that predates the Katana, instead of a Wakizashi or Tanto for the act.

Kanshibara: This type is witnessed by the samurai’s immediate family members. It's often a highly private affair, steeped in both familial and cultural significance.

Kamabara: This form is performed sitting on a straw mat, known as "Kamaza." It is one of the more traditional forms and involves several specific rituals.

Kagebara: This form is performed in complete solitude, often in a place where the samurai would not be discovered until after death. There is no second in this type of Seppuku.

Each variant has unique elements and symbolic meanings. However, the essential principles of honor, courage, and ritualistic formality are common in all.

Is seppuku a voluntary act?

In the context of feudal Japan, Seppuku was often a voluntary act, but this was not always the case. Primarily seen as an act of atonement, Seppuku could be chosen by a samurai to preserve honor, rectify shame, or avoid capture. However, it was also sometimes mandated by authorities as a form of capital punishment or as a requirement following the defeat of one's lord.

Voluntary Seppuku: A samurai could commit Seppuku of their own accord for various reasons, such as:

- Personal honor: To atone for failure or mistakes.

- Philosophical or ethical reasons: Aligned with the principles of Bushido, the samurai code of conduct.

- Following a lord's demise: Known as "Junshi," some samurai chose to follow their deceased lord in death.

Mandated Seppuku: In some cases, Seppuku was ordered as a form of punishment for a crime or misconduct. However, even in these instances, the act was seen as more honorable than execution:

- Judicial sentence: For crimes such as corruption, incompetence, or defeat in battle.

- Commanded by a Daimyo or Shogun: As a way to uphold feudal law and order.

Therefore, while Seppuku was often voluntary and a chosen act of atonement, it could also be a non-voluntary act imposed by higher authority.

Why did the samurai split the belly?

The act of splitting the belly, or "Hara-Kiri" (literally "belly-cutting"), during Seppuku has deep-rooted significance within the framework of samurai culture and the Japanese concept of honor. It is important to recognize that this method was chosen not for the sake of brutality but for profound symbolic and philosophical reasons.

Embodiment of Courage and Honor:

The abdomen was traditionally considered the seat of the spirit and emotions in Japanese culture. Cutting open the belly was a demonstration of a samurai's courage and resolve. It was a very painful and slow form of death, and completing the act without revealing agony was deemed the ultimate testament to a samurai's willpower and discipline.

Ritualistic Nature:

The act of cutting the abdomen in a specific pattern, usually left to right and then optionally a second cut upwards, was steeped in ritual. The presence of a "Kaishakunin" (a second), usually a close associate, was to ensure the ritual was performed correctly and to administer a final, decapitating strike that would end the samurai's suffering.

Purity and Atonement:

The act was also seen as a form of purification. It allowed the samurai to atone for failures, restore their family's honor, or exhibit ultimate loyalty to a feudal lord.

Public Statement:

Seppuku was often a public ceremony, witnessed by friends, family, and sometimes even enemies. The way in which the act was carried out could restore honor not just to the individual but also to the family and clan.

Seppuku and Harakiri Myths

The topics of Seppuku and Harakiri are often shrouded in mystery and misconception, especially for those who aren't deeply familiar with Japanese culture and history. The popular media, movies, and even some historical accounts sometimes offer an overly dramatized or simplified view. Here's a look at some of the myths and misconceptions surrounding these practices.

1. Only Failed Samurai Committed Seppuku: Contrary to popular belief, Seppuku wasn't just for disgraced or failed samurai. It was also a way to protest against corruption, make a political statement, or even follow a deceased feudal lord into death.

2. It Was Always Voluntary: Although Seppuku is often considered a voluntary act, there were instances when it was essentially a form of capital punishment, imposed upon the samurai by higher authority.

3. Women Also Committed Seppuku: While it is true that women related to samurai (known as "Onna-bugeisha") sometimes performed a similar act known as "Jigai," it was not the same as Seppuku and did not involve the same ceremony or formality.

4. It Was Quick and Painless: Contrary to this belief, the act was painful and gruesome. That's why a Kaishakunin, a second person, was often present to perform a decapitation to quicken the process.

5. Always Done in Private: While many instances of Seppuku were done in a private setting, some were highly public affairs, intended as a demonstration of courage, conviction, and honor.

6. Seppuku Was Commonplace: Though well-known, it was not as commonly practiced as people might think. It was a grave act with significant social and personal ramifications.

7. Only the Samurai's Own Sword Was Used: Contrary to popular belief, the samurai did not always use their main katana for Seppuku. More often, they used a shorter blade like a wakizashi or even a specialized knife.

Was it Only Samurais Who Could Commit Seppuku?

The act of Seppuku is most closely associated with the samurai class of Feudal Japan. However, it is a misconception to believe that only samurais could commit Seppuku or Harakiri. Although the act is deeply entrenched in samurai culture and the Bushido code, there have been instances where individuals outside of the samurai class have committed this form of ritual suicide, particularly in extraordinary circumstances.

For example, during certain periods of Japanese history, it was not uncommon for retainers or even commoners to commit Seppuku to follow their lords in death, known as "junshi." This practice, though not as regulated or formalized as the samurai's Seppuku, signifies the extent to which the concept of honor and the ritualistic form of suicide permeated through different layers of Japanese society.

In some rare instances, women associated with the samurai class also participated in a form of ritual suicide, known as "jigai," to avoid dishonor or capture. However, jigai was distinct from Seppuku or Harakiri in terms of method and ceremony.

Both acts fundamentally aimed at preserving or regaining honor and were typically limited to those who were part of, or closely associated with, the warrior or samurai class.

In modern Japan, the practice is considered illegal and is not performed. Despite this, the cultural imprint of both Seppuku and Harakiri remains a topic of historical and ethical discussion within the broader context of Japanese history and samurai culture.

Did female samurai commit seppuku

While the title "samurai" is conventionally attributed to men, women hailing from samurai families and trained in the martial arts were referred to as "Onna-bugeisha". Though they didn't carry the official designation of "samurai," they were nonetheless considered part of the samurai social class. This status granted them the privilege to participate in combat and protect their households. However, the ritual of Seppuku was traditionally a male practice, rooted in the samurai code known as Bushido.

Female members of the samurai class who chose to end their lives did so through a different ritual known as "Jigai." Unlike Seppuku, which involves abdominal cutting, Jigai involves cutting the arteries of the neck. Women would tie their knees together so that their bodies would be found in a dignified position, even in death. This ritual was often performed by samurai women to avoid being captured or subjected to dishonor, particularly during a siege or invasion.

It's essential to note that while both Seppuku and Jigai were forms of ritual suicide, they were distinct in method, symbolism, and societal perception. The practice of Jigai indicates that while female members of the samurai class did not traditionally commit Seppuku, they had their own ritual for ending their lives in a way that was considered honorable within the framework of their societal roles and expectations.

Who is the last to commit harakiri

The most recent high-profile instance of either Harakiri or Seppuku involves Yukio Mishima, a renowned post-war Japanese novelist. On the 25th of November, 1970, Mishima, along with four individuals from his self-formed militia, the Tatenokai, orchestrated an unsuccessful coup d'état with the goal of reinstating the Japanese emperor's authority. After the coup attempt failed, Mishima committed Harakiri in the office of the Japan Self-Defense Forces' Eastern Command. His follower, Morita, served as his second (Kaishakunin) but failed to decapitate him cleanly, requiring another individual to finish the act.

It's important to note that Mishima's act was not a reflection of mainstream Japanese culture during his era. Rather, his undertaking of Harakiri was a bold political statement, aimed at protesting what he saw as the erosion of traditional Japanese values following World War II.

While Mishima's case is the most recent high-profile example of Harakiri, it would be difficult to assert that no other instances have taken place afterward. There could very well be lesser-known or unrecorded cases that have escaped public attention. However, the act has largely fallen out of practice and is not considered an accepted or honorable form of death in modern Japan.

Is either Harakiri or Seppuku still practiced today

The practice of Harakiri or Seppuku is largely obsolete in modern Japan and is neither legally sanctioned nor considered an honorable form of death in contemporary Japanese society. These ritualistic forms of suicide have largely faded away, replaced by modern legal and cultural norms.

Historically, Seppuku served as a means for samurai to reclaim their honor or the honor of their families, particularly in situations involving defeat or disgrace. However, contemporary Japanese culture has evolved, and such drastic acts are no longer socially sanctioned as they were in earlier times. Present-day Japanese law explicitly prohibits suicide and self-harm, reflecting a shift in societal attitudes towards these extreme practices.

While the fascination with samurai culture and the Bushido code is still prevalent in many aspects of Japanese society, from films to literature, the practice of Harakiri and Seppuku is generally considered a dark aspect of feudal history. Some may still romanticize these acts, but they are not in line with contemporary views on human rights and personal freedom.