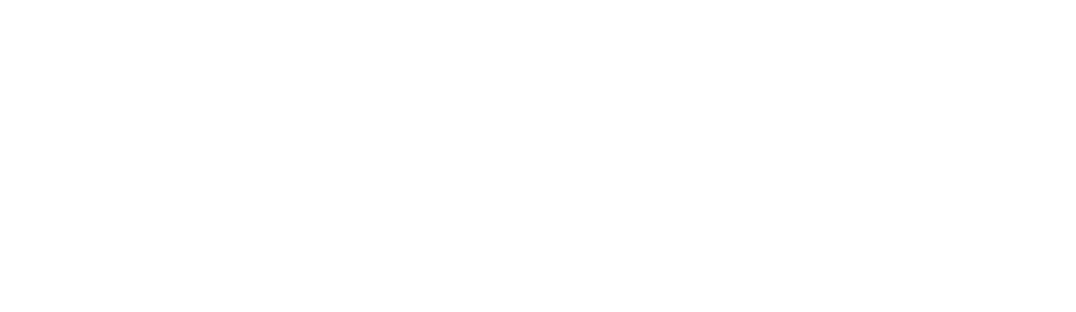

What is a Chonmage?

A Chonmage (丁髷) is a traditional Japanese hairstyle most commonly associated with samurai during the Edo period (1603–1868). It involves shaving the top of the head while leaving the sides and back long, with the remaining hair oiled and tied into a small, rounded topknot that sits on the crown of the head. This samurai hairstyle served practical purposes, such as securing the helmet (kabuto) worn by samurai in battle. The shaved crown prevented discomfort, while the topknot kept the helmet stable. Over time, the chonmage evolved into a symbol of status and honor in samurai culture.

Picture: Chonmage (hairstyle)

Practical purposes of the Chonmage

- Prevention of enemy grabs: Made it harder for enemies to grab the hair during combat.

- Clear vision in battle: Prevented hair from falling into the eyes, ensuring unobstructed sight.

- Ventilation under the helmet: Improved airflow beneath the kabuto, crucial in Japan's hot and humid climate.

- Cushion for the helmet: Provided natural padding for added comfort when wearing the kabuto.

- Lice prevention: Shaving the crown helped reduce the risk of lice infestations.

The History of the Chonmage

Chonmage in the Heian Period: Origins

The chonmage dates back to the Heian period (794–1185). During this time, aristocrats wore cap-like crowns as part of their formal attire, tying their hair in the back to secure the cap. When the samurai class emerged, they adapted this style for a practical reason, to stay cool and comfortable while wearing their helmets in Japan’s humid climate. The shaved crown allowed better airflow, with some kabuto even featuring a small opening at the top to enhance ventilation. Additionally, the topknot acted as a cushion between the head and the helmet.

Picture: Kabuto helmet with a hole on the top

This hairstyle evolved over centuries, and by the Warring States period, it had become essential for battle. A shaved crown prevented the hair from falling into the samurai’s eyes and made it harder for enemies to grab their hair during combat. Thus, the chonmage was both practical and symbolic.

Chonmage in the Edo Period: A Symbol of Nobility

During the Edo Period (1603–1868), as Japan experienced a prolonged era of peace, the chonmage took on a more formalized role in society. It was no longer just a practical hairstyle but a deeply symbolic one, signifying the samurai's elevated status and their cultural significance in a hierarchical society. The shaved crown symbolized humility and discipline, while the tied topknot served as a visual identifier of their class and legacy.

Even commoners began to adopt the chonmage as a mark of respect for the samurai class. However, their topknots were smaller and less elaborate, reflecting humility and acknowledging the samurai’s higher social standing. During this period, over 100 variations of the chonmage existed, with each style reflecting the wearer’s rank, region, or profession.

Picture: Chonmage styles

The Decline of the Chonmage

The Meiji Restoration of 1868 marked a turning point. With Japan’s rapid modernization and the dissolution of the samurai class, traditional hairstyles like the chonmage were largely abandoned. In 1871, a government decree mandated short hair and Western clothing for all Japanese citizens. The chonmage, along with other traditions of the samurai, was officially outlawed as part of Japan’s modernization efforts.

Picture: Samurai with a chonmage hairstyle

Despite its decline, the chonmage remains an enduring cultural symbol. It is preserved in sumo wrestling, where wrestlers maintain the tradition as part of their ranking system and rituals. Additionally, the hairstyle frequently appears in kabuki theater, period dramas, and historical reenactments, serving as a reminder of Japan’s rich feudal heritage. The chonmage represents not only the practicality of early warrior culture but also the deep cultural and symbolic significance of tradition and identity in Japanese history.